News

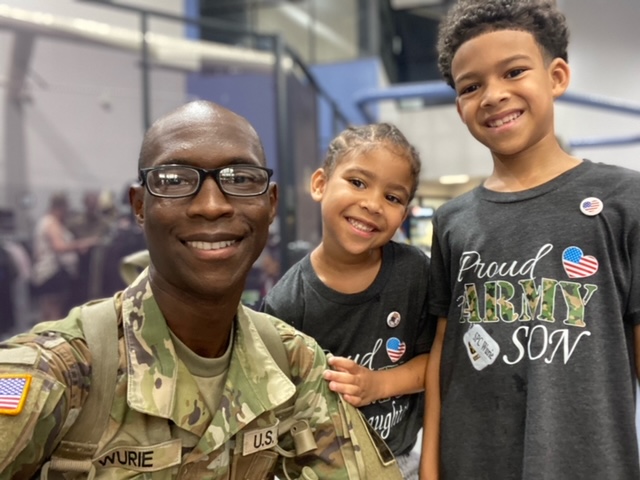

Boots on the ground: Chernoh Wurie adds Army National Guard to a growing list of professional experiences

by David Slipher

A couple of years ago, Chernoh Wurie was driving with his family when they watched the procession of an Army National Guard vehicle convey. Wurie, an assistant professor of criminal justice at the Wilder School, remarked half-jokingly to his wife, “I’d love to do that someday.” On another occasion at the beach, a passing Coast Guard helicopter stirred similar feelings for this persistent “someday.”

That someday became a reality in February, when Wurie officially signed on for a post with a ground transport unit. He’d grown somewhat restless and wanted to “get back in action” in the field. At 41, he had to receive a special age exception waiver. His extensive experience in criminal justice practice and theory made him an ideal candidate and after a few congressional letters of recommendation, he officially became one of the oldest service members to attend basic training.

Getting back to the basics

When Wurie deployed for basic training in June, he was eager to become part of a new team again. He was assigned to Delta company, made up of between 150-200 enlisted soldiers. He was missing the feeling of service and familiar camaraderie he’d developed with his law enforcement community.

Physical activity was another component he was excited about. Delta company would wake up at 4:30 in the morning, conducting drills, going for runs and doing countless pull-ups. “I went into good shape, but I came out at great shape,” Wurie said. “I'm in the best shape of my life. It was the mental part that was hard — as a 41-year-old male being in around a bunch of 20-year-olds. I felt like, ‘you all are the age of my students!’”

Wurie tried to fly below the radar, but the younger cadets quickly ferreted out both his age and seasoned experiences. As a result, he was volunteered for a lot of leading roles such as platoon leader and team lead for the Soldiers Against Sexual Assault (SASH), which helped build relationships with his unit.

Accountability and group solidarity are a strong part of military culture. Attention to detail was the difference between successful barracks inspections and punishment for anything short of perfection. If there was an individual violation of procedure, such as a single messy locker, the entire company would bear the reprimand together. In one particular incident, the obscure and mentally anguishing punishment was scrubbing and cleaning a pile of rocks.

“This felt like the lowest point in my life,” he recalled. “Sitting out here wiping and washing rocks because somebody did something stupid. But the Army is about teamwork. I gained a profound appreciation for our military forces knowing what I just went through and having the support of my family, friends and colleagues.”

It wasn’t a successful experience for all. Wurie estimates that out of the nearly 1,000 total recruits, only about 800 graduated. For some, the National Guard culture wasn’t a good fit. But for Wurie, the best part was dramatically walking through the smoke at his graduation ceremony while his family cheered him on.

“I did this for my kids. My son is only seven years old, and I did it for him to wake up one day and be like, ‘you know, my dad joined the army at 41. ‘I can do anything I want in this world.’ To get my son to brag about me, that’s dad points, you know.”

“I did this for my kids. My son is only seven years old, and I did it for him to wake up one day and be like, ‘you know, my dad joined the army at 41. ‘I can do anything I want in this world.’ To get my son to brag about me, that’s dad points, you know.”

Intersecting real-world expertise with academia

Before joining the National Guard, Wurie spent more than a decade as a police officer in Prince William County Police Department and has always made good use of his field experiences. He’s served as a patrol officer, crisis intervention team member, crime scene technician and police planner.

With a passion for emphasizing effective community policing, he authored the book “Impact: A Compilation of Positive Police Encounters” as well as a textbook entitled “Introduction to Policing: Public Perceptions Versus Reality.” Wurie views increased diversity in police departments, especially for women and LGBQTIA officers, as a transformative tool that impacts awareness and overcomes cultural stereotypes, both for officers and the public. It’s a critical path forward for policy reform, and he has seen significant progress in these efforts since he began police service.

He instructs Introduction to Policing, Principles of Criminal Investigations, Violent Crime Scenes Investigations, Race, Crime, and Justice and Criminalistics. Wurie is also the chair of the Henrico County police chief’s advisory board. In this role, he serves as a special consultant on historic and current policing practices for new recruits and in-service officers.

As a burgeoning police officer, Wurie was not aware of the origins of organized policing in the South, which began as slave patrols. It’s a well-researched history that he doesn’t shy away from in his training curricula today; he uses it to build awareness and reframe the mindsets of officers.

Developing students’ skills and resources

Wurie is very direct when it comes to sharing his experiences with his students. He utilizes material examples he’s collected over the years, such as redacted crime scene images he personally captured.

He bluntly informs his students at the start of each course, “If you get queasy… you might not want to be in this class.” As a result, “some of them would drop the class because they don't want to see things like that, but a majority of them will stick around and say, ‘we want to see this.’”

I'll tell my students, ‘I'm a former police officer. So I may be a little bit biased about some things. Call me out. If you think I'm biased, let me know.’ And sometimes, they have called me out.”

Students also gain insights into many non-traditional resources for police officers, like trauma counseling and mental health support. As a police officer, Wurie made good use of employee assistance programs where he could talk to counselors about his feelings and mindset. These types of services are now mandatory protocol for most agencies when an officer is involved in a violent or traumatic situation. Wurie has lost three friends to suicide and sees support services as vital safety nets. Officers are also trained to look for crisis warning signs amongst their peers.

“These are things we teach,” Wurie said. “I teach them how to handle those things and how to separate those feelings from work and personal life because they’re going to be dealing with a lot of things.”

In his classes, Wurie challenges students to engage in critical reflection to better understand the reality of law enforcement and related aspects of the criminal justice system. He pushes his students to question everything and encourages dialogues amongst students of differing perspectives.

“I show them all sides of the law in my classes,” he said. “I show them mistakes that officers have made. And I show them where officers have done the right thing. I'll tell my students, ‘I'm a former police officer. So I may be a little bit biased about some things. Call me out. If you think I'm biased, let me know.’ And sometimes, they have called me out.”